Sepsis Awareness Month — Learn About Sepsis and You May Save a Life!

Decipher Your Health exists because Karin and I had the good fortune of meeting through our work with Sepsis Alliance – I wrote content for the site, among other things, and Karin is on the Board of Directors. As we worked together over the years (and met in person at a Sepsis Heroes Gala!), we learned that we had similar ideas and opinions about optimal patient care and what people need to get the care they deserve. One day we were chatting about some of our work, and we came up with the idea for Decipher Your Health. So, given how Sepsis Alliance brought us together (how else would an emergency physician in California and a nurse in Quebec meet?), it seems fitting that we highlight Sepsis Awareness Month and World Sepsis Day.

So, what is sepsis?

Let’s do a pop quiz. Here are two questions:

-

What is sepsis?

A) A blood infection

B) An infection in a specific part of your body, like your hip, lungs, or skin

C) Your body’s reaction to an infection

D) A contagious disease

The answer is C.

A and B are both incorrect because sepsis is not an infection. Sepsis is your body’s toxic inflammatory response to an infection.

When you contract an infection, your immune system starts a chain of events that is supposed to fight it off. This is why you may feel swollen lymph glands or have a fever. Often, your immune system is successful, especially when fighting viral infections. Other times, you may need help with an antimicrobial. Antimicrobials are medications that fight infections, such as:

- Antibiotics, for bacterial infections

- Antivirals, for viral infections

- Antifungals, for fungal infections

- Antiparasitics, for parasitic infections

However, sometimes your immune system can go into overdrive. Instead of your body fighting off the microbes (germs) that are making you sick, your immune system starts to attack itself as well as the microbes. This causes a cascade of events that can lead to sepsis.

D is also incorrect because sepsis itself is not contagious. The infection that caused it might be, but not sepsis itself.

-

How common is sepsis?

A) Sepsis is rare

B) It’s not uncommon, but it only affects patients in the hospital

C) It’s not uncommon, but it only affects people who have an illness like diabetes or cancer

D) It’s common

The answer is D. Sepsis doesn’t only affect people in the hospital or those who are ill. It affects up to 1.76 million people in the U.S. each year, with at least 350,000 adults dying from it.

People who have chronic health conditions, like diabetes, or are being treated for others, like cancer or autoimmune diseases like psoriasis or lupus, are at higher risk of getting sepsis, but anyone can get it, regardless of how healthy they are.

Sepsis can be prevented in many cases

Any infection, from an infected paper cut to pneumonia, can cause sepsis. Any type of infection – bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic – can cause sepsis. So, it stands to reason that if we prevent infections from occurring in the first place, we can prevent sepsis. We can also significantly reduce the risk by treating infections quickly and effectively.

Here are some basic infection prevention tips

Get all recommended vaccines for both adults and children.

For example, measles is a preventable childhood disease. Children who get measles often recover without lasting effects, but complications include encephalitis (infection that leads to brain swelling), ear infections, pneumonia, and even sepsis.

Influenza, which requires a yearly vaccine, kills between 12,000 and 52,000 people in the U.S. annually. It also causes severe enough illness that over 700,000 people need to be hospitalized.

Wash your hands well.

This message was loud and frequent throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. But it remains essential as it also reduces the risk of contracting other infections, such as the flu, colds, and others. Wash after using the bathroom, when you’ve been outside the house or office, after handling animals or their excrement, before preparing and consuming food, and whenever they may be dirty.

Avoid people who are sick.

If you must be around someone who is sick or you are in a crowd, consider wearing a mask to protect yourself. Dispose of the mask right after use and wash your hands well.

If you have an infection or suspect you might, seek medical help. Your healthcare provider will determine if you will likely get better with time, or if need an antimicrobial or other treatment. That said, if you develop a high fever, confusion, and other worrying symptoms, contact your provider again as soon as possible.

If you get a prescription for an antibiotic or other type of antimicrobial, ask how long it will take before you start feeling better. If you don’t start feeling better within that time, you should let your doctor know. You may need a different medication.

Even if you start to feel better right away, you still must finish the medication as prescribed. Feeling better doesn’t mean the germs are gone. Microbes can linger and flare up again if you stop taking the antimicrobial too soon. They can become harder to treat as some may become resistant to medications. This is called antimicrobial resistance, or AMR.

How can you tell if you have sepsis?

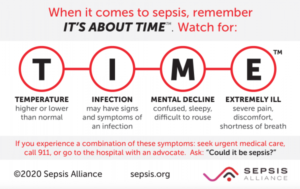

There is no test for the condition. Doctors diagnose it based on information such as if you have an infection and your symptoms. You can suspect sepsis if you have a combination of any of the following:

In addition, you could be or have:

- Shivering, feeling very cold

- Clammy skin

- Rapid heartbeat

- Low blood pressure

If you suspect that you or someone you know may have sepsis, this is a medical emergency. As the TIME card says, seek immediate medical help.

For more information on sepsis and related issues, like post-sepsis syndrome, visit Sepsis.org.

Disclaimer

The information in this blog is provided as an information and educational resource only. It is not to be used or relied upon for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

The blog does not represent or guarantee that its information is applicable to a specific patient’s care or treatment. The educational content in this blog is not to be interpreted as medical advice from any of the authors or contributors. It is not to be used as a substitute for treatment or advice from a practicing physician or other healthcare professional.