Is Dr. Google Reliable?

Google is the number one search engine (80% of market share), so it didn’t take long for people to refer to health information internet searches as consulting “Dr. Google.” According to one site, Google gets 1 billion health questions a day. Some people search to get an idea of what they may have or to learn about what they were just diagnosed with, while consulting Dr. Google are “online diagnosers,” trying to determine what they have on their own. Sometimes they are correct, but often they’re not.

Why is this a problem? If you’re wrong, your healthcare provider (HCP) will correct you, right? True, but if you self-diagnose incorrectly, you may think your illness or condition is much more serious than it is. This could lead to anxiety, stress, depression, and even bad decisions before your HCP can correct you. Or your self-diagnosis might be that you have something minor that will go away on its own. As a result, you may not make an appointment because you are trying to manage on your own. All the while, your illness or condition could be getting worse.

Either way, online diagnosers can make their HCP’s job harder. When patients come to the office believing one thing, the HCPs must explain why they aren’t seriously ill or sicker than they believe. And, sometimes, the patients don’t believe the HCP.

That said, consulting Dr. Google and checking your symptoms online isn’t necessarily bad, as long as you don’t believe everything you read and plan to see your HCP anyway.

Looking for Reliable Information

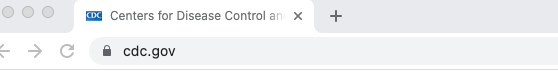

There are several ways you can verify a site’s authenticity and reliability. First, look at the ending of the URL (web address). Sites that end with .edu and .gov are considered trusted sources. Sites with .edu come from schools such as Stanford University or Johns Hopkins University. The ones ending with .gov come from state or federal government sites.

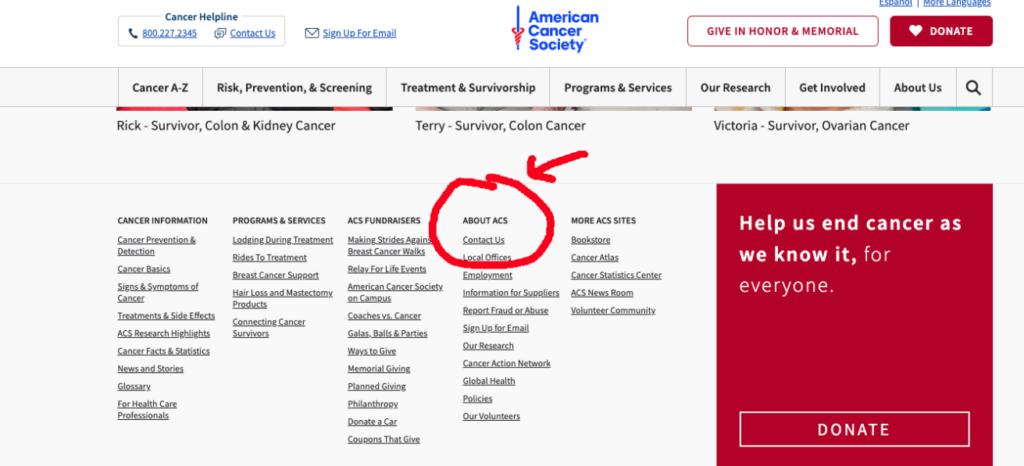

Sites that end with .org used to be considered relatively safe, with some caution. The domain was only for sites run by non-profit organizations, like the American Heart Association (www.heart.org) or the American Diabetes Association (www.diabetes.org). Some hospitals, like the Mayo Clinic, also use the .org domain. This changed, though; now anyone can buy a .org address and set up shop.

The foundation or association sites can still be a good source of information. The thing to keep in mind is that the information can be slanted toward a particular point of view, or the information may be outdated. For example, given how quickly healthcare had to adapt during the pandemic, what we knew about some things in January 2020 is very different from what we know now. So try to see when the site page was last updated.

What about the .com sites? Should you avoid them because they’re commercial? Not necessarily, but be careful. There are things to watch for that will help you decide if it’s a reputable site.

Who Is the Publisher?

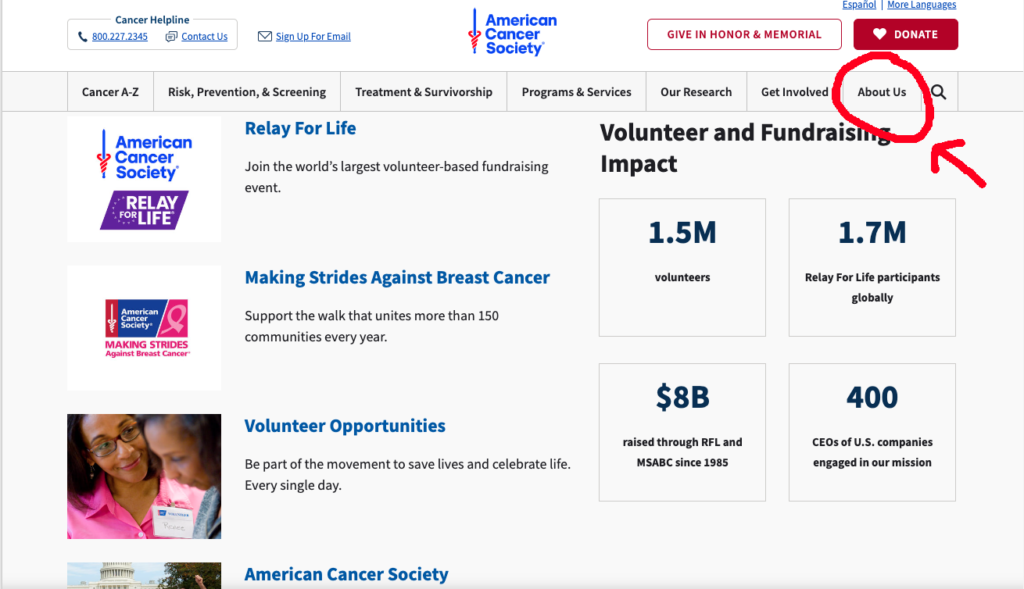

Check the “About Us,” sometimes in the tabs at the top, but almost always at the bottom or footer. The About section usually describes who owns the site, who edits it, and if there are any sponsors. It may list writers’ or contributors’ too, maybe with bios. Who are those writers? Do they have credentials? Is the information medically reviewed?

Another thing to think about is the reason someone may own a site domain. For example, pharmaceutical companies may buy a new drug’s name as a domain to push its new drug in front of as many people as possible.

Check out some articles to see when they were published. How old is the information? Do the articles have references so you can go back and see where they got their facts and statistics? When discussing studies, do they use reliable sources like Nature, JAMA, and other medical journals? Is the site more blog-like, with opinions instead of facts? Who sponsors the site? This is important because it can skew the information.

And, of course, there are some red flags to watch for:

- No contact information

- Spelling and grammar mistakes

- Their own products for sale

- Offers of cures

- Comments that include “always” and “never,” such as “X disease is always cured if you eat this.”

“Luck favors the prepared mind” – Louis Pasteur

After completing your research with Dr. Google, talk to your family about what concerns you and what you’ve found. Has anyone else in your immediate family experienced the same things? Your online research and family history can help prepare you for your appointment with your HCP.

When you get to your appointment, with your concerns, show your HCP your research – within reason. Don’t bring in reams of printouts, but a brief outline of what you learned.

What if your HCP seems frustrated by the work you have done or is dismissive? Dr. Molander tells patients that there should be no one MORE invested in their health than the patient. One approach to a feeling that you and your HCP are in this together is to say that you wanted to make sure that you “weren’t wasting the provider’s time” and that you wanted to make sure that you were prepared with questions and concerns to make optimal use of your time together.

The Final Word

If you find yourself more confused and scared after your time on the web, consider clearing your cache search so the next time you log on, your search history doesn’t trigger algorithms that may send you ads promoting new medications or diets, or even show you TikTok videos of disasters in the ER.

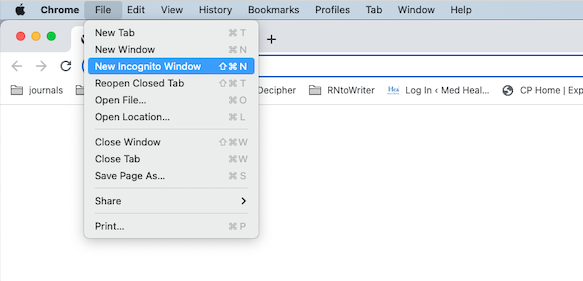

Alternately, consider searching for sensitive information, like your health, using an incognito window. All the major browsers have these private browser windows. They don’t save your activity, browsing history, or cookies, so you won’t find targeted ads based on what you were looking for. This is particularly useful if you share a device with someone else.

The internet can be an excellent tool for learning and connecting, but we can never forget that there are those out there who are ready to take advantage of vulnerable people. Protect yourself.

Disclaimer

The information in this blog is provided as an information and educational resource only. It is not to be used or relied upon for diagnostic or treatment purposes.

The blog does not represent or guarantee that its information is applicable to a specific patient’s care or treatment. The educational content in this blog is not to be interpreted as medical advice from any of the authors or contributors. It is not to be used as a substitute for treatment or advice from a practicing physician or other healthcare professional.